My view: the corporate tax should be zero. Not just a zero rate, but the tax should be abolished. Lowering a rate is just an invitation to renegotiation, and a quick raise when the next party takes over. Lowering a rate keeps all the lobbyists around to keep all the exemptions going. To reduce a tax, you must follow the advice of a zombie movie -- kill it, and drive a stake through its heart. Burn the code, delete it from the hard drive.

In my best guess, the tax is entirely really paid by consumers in higher prices and workers in lower wages. However, it works best only with a shift to a consumption tax (progressive if you wish) on individuals.

In the news,

Marginal Revoultion has a short piece on eliminating the corporate tax, linking to Utah Senator

Mike Lee and to Matt Yglesias,

Scrap the Corporate Income Tax. When I agree with Matt on something, a rare event, I like to celebrate. Matt:

"Closing loopholes while lowering rates would still leave the basic structure in place, with well-connected companies ferociously lobbying for their tax breaks. We need something much bigger and tougher that corporate income tax reform: an alternative source of revenue that will let us do away with the corporate income tax entirely.

.. Just give up. Though the corporate income tax as presently constructed supports a small army of accountants, tax lawyers, lobbyists, and CNBC talking heads, it doesn’t raise very much revenue.

Rather than trying to mend the tax, we ought to end it and replace it with something else.

Pick who or what we want to tax, and tax it deliberately."

Lee writes

"..what would a tax system that puts American workers first look like? It would start with a cut in the federal corporate tax rate. Not to 25 percent or 15 percent, but to zero. Eliminate it altogether."

Issue 1 Incidence

What, shouldn't corporations "pay their fair share?" As both authors recognize, corporations bear no tax burden. Every cent of corporate tax comes from people -- from higher prices for products, lower wages for workers, or lower profits for investors. A corporation is just a shell, money goes in and money goes out.

The difference between who pays a tax and who bears the burden of taxation is one of the nicest lessons of econ 101. The clearest example is sales tax. Stores "pay" the sales tax, but it's clear to every shopper that they "bear the burden" -- that prices would be exactly that much lower without the tax. (This may not be true or exactly true, but it's a good example nonetheless as people see it that way.) But if a sales tax is passed on completely in higher prices, and is thus borne by consumers, the same principle applies to corporate taxes as well.

So who bears the burden of the corporate tax -- consumers (higher prices), workers (lower wages), or investors (lower profits?)

I agree with Matt (again!)

Who ultimately pays those corporate income taxes? This is a fascinating question in the economics literature, and a bit of a black box, with nobody quite sure who’s paying or why

Lee explains

It may seem ironic that a populist, pro-worker tax reform could begin with what sounds like a handout to corporations. But it’s true. Remember, the corporate tax is not assessed on some villainous collection of “Wall Street fat cats.” ... The corporate income tax takes money that would otherwise be some combination of investors’ dividends and workers’ wages. [JC: and consumer's lower prices.]

Economists differ on the precise ratio, but the consensus is that lost wages make up between one-quarter and one-half of corporate tax revenue. (According to one recent study, it may be even more.) But whatever the proportion, we know that eliminating the corporate tax would immediately liberate every penny of American workers’ share of it, and in short order boost take-home pay in every industry across the country

Lee links to

Major Surgery Needed: A Call for Structural Reform of the U.S. Corporate Income Tax

by Eric Toder and Alan D. Viard, who find workers bear 50% of the corporate tax, and

Corporate Tax Burden on Labor: Theory and Empirical Evidence by Aparna Mathur and Matt Jensen, interesting papers on the subject.

The principle is pretty straightforward, and I think points to the major mistake in current thinking. Who bears a tax? He or she that cannot get out of the way! (The inelastic demand in econospeak.)

Consumers? If US corporations face, say, strong competition from non-corporate business or foreign corporations on prices, they won't be able to raise prices to pay the tax. But don't confuse an individual firm's ability to raise prices with the whole industry. When all businesses must pay tax, and all privately held businesses must pay a coordinated income tax, and they have to pay it on all goods, there really is nowhere else to go. You can buy less overall and enjoy free things instead -- walks in the park -- but that's about it. So it's a good bet that much corporate tax is paid by consumers in the form of higher prices, just like sales and VAT taxes.

Workers? If companies lower wages overall, permanently, how much less do people work? Not a lot, actually. Poorer people work harder, but given income, people work less for a lower wage. These "income" and "substitution" effects largely offset, so at first pass, the amount of labor overall does not change or if anything slightly increases with lower wages overall. So, lower wages can be passed on.

Capital? The widespread presumption is that the corporate "profits" tax results in lower profits, and thus is borne by Mr. Toppam Hat. I think much of this is a sunk cost fallacy.

Suppose we institute a 35% corporate tax, and suppose corporations as a whole cannot raise prices or lower wages, and they do not shrink in size. Then dividends go down 35%. The stock price goes down 35%. The initial owners of the company lost the entire present value of the corporate tax. But after that, anyone who buys a stock for 35% lower price, getting 35% lower dividends gets exactly the same return going forward. Fast forward 50 years or so, and the current owners are bearing no burden of taxation whatsoever.

You can see the key assumption I made -- that the rate of return new investors demand does not change (just like the assumption prices can't change or wages can't change, which would insulate consumers or workers from bearing the tax). But of all the can't changes, that seems the most reasonable. In a global capital market, trying to get people to give you savings at a lower rate of return is a lot harder than trying to get them to pay more for products or work for lower wages.

Furthermore, there is another avenue out: Save less. If indeed new capital is bearing the burden, people save less. Firms become smaller, to the point that the marginal product of capital equals the old rate of return plus the corporate tax. Then once again consumers and workers are bearing the entire tax, even though no prices have changed. They just get less products and less work. This is the intuition why the optimal tax rates on rates of return is zero, which is the reason for a consumption tax.

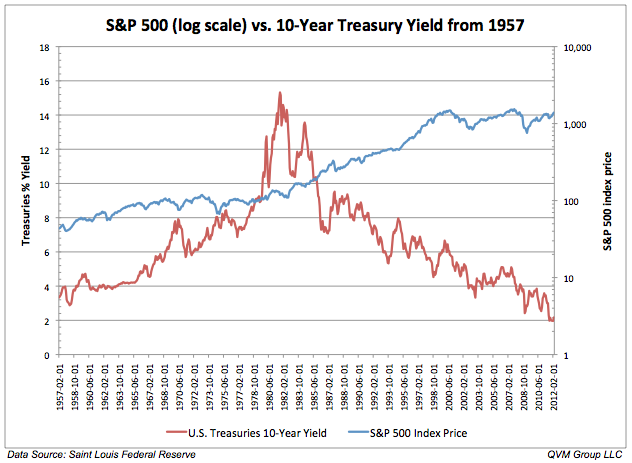

One piece of evidence, I see no difference in average return on stocks or interest rates on corporate bonds through wide variation in corporate tax rates. I also don't know of evidence for big stock price declines when corporate tax rates are introduced. The former suggests the rate of return is the same, and corporate taxation does not therefore get paid by investors. The latter suggests that it is coming out of prices or wages, not dividends in the first place.

So, econ 101 first principles suggest to me that most of the corporate tax is borne by consumers and workers, not by current owners.

We want "science" to guide public policy. If the fact that who pays the tax and who bears the tax cannot be explained and acted on in our public forums, we really are in trouble.

From Toder and Viard I learned an interesting tidbit:

When it comes to the corporate income tax (CIT), there is no standard assumption that is uniformly applied by those agencies [Congressional Budget Office, Treasury, and the Joint Committee on Taxation]. ...economic incidence is not obvious. While the CBO and Treasury have historically assumed that the CIT is borne by owners of capital, the JCT is wary of assigning incidence to any particular group of individuals..... their distribution tables ignore the incidence of the CIT altogether,

We live in an era of great attention on "facts" and "alternative facts" and "science." Every tax reform is followed by agonizing detail of "facts" on just who gains and who loses down to the last $10 -- with essentially no attention to incentives, the economists laments. But those calculations are seldom transparent, they're just big black boxes. Now, one look in to one black box, we find out that distributional effects of corporate tax cuts are

basically made up by arbitrary assumption. Issue 2 ReplacementMatt describes high taxes on dividends, but not with any spirit or detail. I prefer a simple consumption tax, for reasons I'll get to in a minute.

Lee wants to make up the difference with higher investment income taxes rather than a progressive consumption tax

lost revenue could be recouped, at least in part, by raising the tax rates on capital gains and dividends.

Though he points out that even 39.6% Federal income tax is less than the current 50% --"35 percent corporate tax rate, 20 percent rate on capital gains and dividends, and the 3.8 percent Medicare surtax," it's still 39.6% too much (plus state taxes). More later.

I prefer a simple consumption tax, with no income tax at all. It's almost necessary to do this. The corporate income tax is, in a way, one more side effect of the mistake of trying to tax income rather than consumption in the first place.

If we have no corporate income tax, then people rush to incorporate themselves, pay no taxes on the incomes of their corporations, and only take out dividends as personal income when they need to buy something. That's why we have a corporate rate roughly the same as the top personal rate.

The corporate tax comes, I think, from fundamental misconceptions. The first is that corporations are somehow like people, who when taxed bear some burden. No, corporations are just shells or buckets of money, people pouring money in or taking it out bear the entire burden. Second, is that profit is somehow different from the electric bill, wages, or debt. The latter are costs of dong business, the former is a benefit which bears a burden when taxed. I think people have in mind a business completely owned by a person, the business was started long ago, and the person lives on the profit stream. Downton Abbey, say. The error is that businesses need capital just as they need labor and electricity. Profits, paid to capital are a cost of doing business no less than wages or the electric bill. Seen that way, taxing profit is no different conceptually than taxing wage payments, interest payments, or the electric bill.

A lot of the difficulty of lower corporate income taxation revolves around what to do with retained earnings, profits the company makes but does not pay out and instead reinvesting them in the firm. Now we get fancy with investment tax credits, and depreciation schedules, and so forth. You see that Rube Goldberg complexity springing up in Mathur and Jensen, given their statement at the beginning that they didn't want to consider also scrapping the personal income tax. Matt and Lee both want high taxes on dividends and capital gains for the same reason -- though taxing dividends and capital gains is a terrible idea because it taxes rates of return. It also will involve more 401(k), 526(b) and other complex devices to get around the obviously bad idea of taxing rates of return.

No corporate tax, a large consumption tax, no tax on rates of return, fit well together. (No corporate and estate tax also means "non-profit" ceases to mean much. That would be very healthy -- profit vs. nonprofit could relate to the actual organization mission, not exploiting tax laws.)

One easy way to move towards a progressive consumption tax by the way would just be to remove all limits in IRA, 401(k), etc. I think the ideal is a uniform VAT -- with eliminating corporate, income, and estate taxes -- plus on-budget transfers for progressivity.

Issue 3 Border adjustment

The corporate tax reform question has gotten mixed up with the border adjustment issue. Several readers have asked for my opinion. I have to admit I'm confused.

Feldstein likes it Summers hates it. If sold as a VAT, which is border adjusted it makes sense. But it's not a VAT -- wouldn't apply to non-corporate business and, I hope dearly, not to direct imports and services. When I read some of the other blogs it seems like a complex mess ripe for exploitation by clever tax lawyers. Perhaps it's not as bad as a uniform tariff (not much could be worse), but that's weak praise.

Anyway, I've spent a day or so trying to figure it out, and can't get to solid ground. That by itself seems an important weakness. I'm not the smartest person on earth, but I am a reasonably trained economist, and I have put a day into figuring this out. Tax reform ought to be really simple, and transparent to the American people, if for nothing else to put out the smoldering fire that people feel the system is rigged and fancy people with fancy lawyers are getting away with murder.

Most of all, if now is not the time to really do it right, when is? This is surely the one time in most of our lifetimes for a comprehensive, massive simplification of the tax code.