Home » All posts

Irish Behavioural Science and Policy Network Event on Behavioural Economics and Healthcare in Ireland

Posted by Economist Channel on

Friday, February 9, 2018

Label:

Our next session takes place on March 8th in the Economics and Social Research Institute seminar room. It will address the application of behavioural economics and behavioural science more generally in healthcare in Ireland. The event will take place from 12pm to 2pm. It will consist of short opening contributions from four people actively involved in this area followed by a moderated panel discussion, and we will also include time for networking and discussion of potential collaborations. Currently confirmed panels are Dr. Fiona Kiernan from Beaumont Hospital who has been working on behavioural interventions in the area of sepsis, Kirsten Connelly Deputy Director of Communications at HSE, Robert Murphy Senior Researcher at the Department of Health who has been working on the interaction between the health system and patients in a range of contexts, and Dr. Pete Lunn who is the lead researcher in the ESRI Behavioural Economics program. To attend the event, please sign up here. The event is free but registration is required for planning purposes.

Stock Gyrations

Is this 1929, the beginning of the end? Or 2007? Is it 1974, annus horribilis in which the stock market drifted down 40% having something to do with stagflation, and did not recover until the 1980s? Is it 1987, a quick dip followed by recovery in a year? Or just an extended version of the flash crash, when the market went down 10% in a few hours, and bounced back by the end of the day? Are we in a "bubble" that's about to burst? How much does this have to do with the Fed? Of course I don't know the answer, but we can think through the logical possibilities.

(Note: This post has equations, graphs and quotes that tend to get mangled when it gets picked up. If it's mangled, come back to the original here.)

Why do prices fall?

Stock prices fall when there is bad news about future profits, or when the discount rate rises.

The discount rate is the rate investors require, looking forward, to get them to buy stocks. If people require a better rate of return, with no change in their expected cashflows, prices drop.

Stop and think about that a second, as it's counterintuitive. Yes, the only way to get a better return out of the same profits or dividends is for today's price to drop.

Another way to think about it: Suppose all of a sudden there are good profitable opportunities for your money -- bond interest rates rise, or it's a good time to take money out of markets and invest in your company. Well, people will try to move money to those alternatives. But the stock market is a hot potato; someone has to hold the stocks. So stock prices must decline until the rate of return going forward matches the other attractions on a risk-adjusted basis. Good news about returns going forward is bad news about a downward jump in stock prices.

Bad news about cashflows is, well, bad news. The dashed line shifts down. Your stocks are not going to pay off as well as before. Higher required returns are neutral, really, for long-term investors. The price drops today, but the higher returns mean the price will slowly recover, just as long-term government bonds do.

So is this a moment of bad cashflow news or higher discount rate? Most commentary suggests it's not bad news about cashflows. The economy seems finally to be growing, and there isn't anything like a brewing subprime or other problem, as there was in 2007. Maybe we don't know about it, but one certainly doesn't read about it.

So let's think about discount rates. Why might investors require a higher return on stocks? Is it interest rates, a risk premium, and is the Fed behind it all?

Where are we?

Are we in a "bubble'' that is about to pop? Let's start by reviewing some facts. Here is the cumulative return on the NYSE since 1990. (This is the CRSP NYSE. Sadly the data stops 12/31/2017 so I don't show the recent drop. The larger index including NASDAQ shows a larger rise and fall in the tech boom and bust, but is otherwise about the same.)

This graph does not show anything terribly unusual about the recent period. Stocks drift up during expansions, and take a beating in recessions. There are also little blips like the Krugman election panic of November 2016. (Sorry, I couldn't resist.) Why have stocks gone up so much? Well, mostly because the expansion has gone on so long. The recent period is also notable in that the little wiggles are much smaller -- less volatility. That ended last week too.

Update: Thanks to Torsten Slok at DB the last year follows. His point, it's sharp but not all that big.

Next, look at the price-dividend ratio. (For a variety of reasons this is a better valuation measure than the commonly used price earnings ratio. This (CRSP) measure of dividends includes all cash payment to shareholders. No, repurchases don't cause a problem.)

You can see prices were high relative to dividends in the booming 1960s; they really rose in the late 1990s before the big 2000 bust. Then you see the 2008 crisis and recovery, and more recent wiggles. You can see prices fall in recessions, even relative to dividends which also fall in recessions.

Where is the booming stock market? Stock prices relative to dividends have not grown at all since the end of the recession. Well, evidently, dividends have been rising just as fast as prices in the current expansion -- which again weren't rising all that fast anyway. So the main reason stock prices are high is that dividends are high, and people expect that slow growth to continue.

So here we were before the recent drop. Are prices too high? Well, not as much as in 1999 for sure! But P/D is a lot higher than historical norms. Is this the beginning of a drop back to historic levels like 30, or even 20? Or is this a new normal? There is way too much commentary lately that whatever we remember from 20 years ago was "normal" and that things have to go back to that. Not without a reason.

Interest rates and stock prices

To think about this question we need some basics of what determines price-dividend ratios. Over long time periods, the return you get on stocks is the dividend yield -- how many dividends they pay per dollar invested plus the growth in dividends. Over short time periods you also get price appreciation per dividend, but over long time periods, the ratio of price to dividends comes back and price growth is the same as dividend growth. In sum,

So, looked at either as D/P or P/D, we now have the tools to think about what pushes stock prices around.

(There is nothing inherently ``rational'' or ``efficient markets'' about this. Behavioral finance just says the expectations are wrong, for example that people think \(g\) is big when in fact \(r\) is small.)

Stock prices are very sensitive to real interest rates, risk premiums, and growth expectations. At our current P/D of 40, for example, this means \(r-g=1/40=0.025\) or 2.5%. Just half a percent change in expected return or growth rate, \(r-g=0.02\) would mean \(P/D=1/0.02=50\), a 25% rise in stock prices. Conversely, a half percent rise in real interest rates would mean \(r-g=0.03\), a decline to \(P/D=33\) a 16.7% fall. No wonder stocks are (usually) volatile!

Now, to what's going on? If we take growth rate expectations off the table, then stock prices are moving because of changes in interest rates. And small interest rate changes do indeed imply big stock valuation changes -- though, again, take heart because it means the rate of return is higher, as in the first picture.

Does this relationship hold historically? Here is the D/P ratio (P/D upside down) and a measure of long-term real interest rates.

(The problem with 10 year real rates is knowing what 10 year expected inflation is, given that we did not have TIPS. There are lots of other problems too, such as unwinding the liquidity premium in government bonds. Here I used the Cleveland Fed's real rate model, which is in part based on survey expectations. I added the 10 year TIPS yield where we have it to confirm the general pattern of the Cleveland Fed's calculation.)

This is a remarkable graph: The entire rise in valuations from 1980 to 2008 corresponds exactly to the decline in real interest rates.

By this measure, the decline in real rates was huge, from 7% to essentially 0%. Plug that in to \(P/D=1/(r-g)\) and we're done. Stock prices are exactly where they should be.

In fact, by this measure, stock prices are too low. In 2008, real rates kept right on trundling down another two percentage points, but the dividend yield stabilized.

Well, I was careful to say "corresponds to" not "caused by" for a reason. The risk premium and growth expectations changed as well. Arguably the move to a low-growth economy starting in 2000, cutting one to two percentage points off \(g\), offset the decline in real rate. Or perhaps the risk premium isn't as low as we think it is. This isn't just waffling -- the relationship is basically an identity. One of those options must be true. If the dividend yield is 2.5%, and the real interest rate is 0%, then \(r^e-g\) is 2.5%, and has grown since 2000. Either the risk premium has grown 2.5% -- so much for the ``low risk premium'' -- or growth expectations have fallen 2.5%. Or the long-term real rate is profoundly mismeasured here.

More on all this in a minute. But the graph reminds us 1) Real rates have come down a lot, and 2) persistent changes in real rates really are an important part of stock market valuations. Oh, and they have nothing to do with ``risk appetite'' and all that other blather. Stocks are valued like bonds plus risk. We are noticing here that the bond-like component got much more valuable. That alone, not the risk component or the growth component, accounts for two decades of huge price rises.

This actually updates significantly some of my own work, and the asset pricing consensus. The great question why do price-dividend ratios vary so much occupied us a lot in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including myself, John Campbell, Bob Shiller, Gene Fama and Ken French. The rough answer we came to -- pretty much all variation in D/P or P/D comes down to variation in risk premiums, the \(r^e=r-r^l\) term. The underlying fact is that times of high P/D are not reliably followed by higher dividend growth (Shiller), and they are reliably followed by low excess returns (Fama and French). If you add it up, the risk premium effect neatly accounts for all the variation in P/D (Campbell and Shiller, me).

Well, in the data up to 1990, we didn't see much persistent variation in real rates of interest, and what we did see was not correlated well with stock prices. Well, that was 1990, and now is now. This graph suggests that in fact a lot of the recent variation in P/D corresponds to lower real interest rates. Also, it's the low frequency, decade to decade movement in P/D that is not well accounted for by any models. An academic version of this observation needs to be written.

Practical bottom line: The stories that the recent stock price decline comes from rising long-term real interest rates make sense. They might be wrong, but they make sense. That's saying a lot more than most of the other stories being bandied around right now.

Interest rates, growth, stock prices, and the Fed.

The story is not that easy however. We have to think about real interest rates \(r\) and growth \(g\) together. And there is this puzzle to answer -- how can it be that good news about the economy sends the market down? If \(P/D=1/(r-g)\) more \(g\) should raise \(P\), no? It should shift up the dashed line in my first graph?

No. We have to think about where real interest rates come from. One of the most basic relationships in economics is that higher growth means higher real interest rates. If everyone will be richer in the future -- growth -- they need an incentive to save and not blow it all today. And growth means a higher marginal product of capital, and hence higher interest rates. As a simple equation, \[ \text{real rate} = \gamma g \]where \(\gamma\) is a parameter, usually between about 1/2 and 2, and get ready for a bar fight at the AEA convention over just what value to use. 1% higher growth means about a half percent to two percent higher real interest rate.

(There is a second term too, important in understanding things like the financial crisis. More uncertainty means lower interest rates. Not today.)

If \(\gamma=1\), if one percent growth means one percent higher real interest rates, then higher growth has no effect at all on stock prices or price dividend ratios. (\(D/P = r^l + r^e - g.\) Raise \(r^l\) and \(g\) by the same amount.) If, as I think is more likely right in this case, \(\gamma>1\), then higher growth lowers stock prices. Yes. Higher growth means a higher discount rate as well as more dividends. The discount rate effect can overwhelm the cashflow effect.

This has nothing to do with the Fed. There is a natural human tendency to look for Agency, for some man or woman behind the curtain pulling all the strings, and these days that means the Fed. For example, the WSJ Editorial on stocks:

Yes, the papers like to say that higher growth will induce the Fed to raise rates. The Fed can put a finger in this dike for a bit if they want to, but even the Fed cannot long fight the positive or negative relationship between real growth and real interest rates.

So it makes perfect sense, at least as a logical possibility, that more growth lowers stock prices! Again, this is like my lower line in the first picture -- and actually a bit better because we also raise the terminal point. If this is what happened, well, regret that you didn't see it happening and stay out during the dip, but be reassured the market will make it back.

Risk premiums

What about the ``unusually low risk premium''? Aren't the Fed's ``massive QE and abnormally low interest rates distorting risk premiums and causing asset price bubbles?'' (The best definition of ``bubble'' I can muster is a risk premium that is too low, distorted somehow.)

Here is the contrary view. We are at the late summer of the business cycle. The economy is relatively healthy, at least if you're a stock market investor. (Many of these own companies.) Economic volatility is still at an all time low. Bonds are still giving pretty atrocious real returns. Yeah, stocks look pretty healthily priced -- as you contemplate your \(P/D = 1/(r^l + r^e - g)\) it looks like the extra return from stocks \(r^e\) is pretty low. But what else are you going to do with the money? You can afford a little risk. Contrariwise, the same investors in the bottom of the great recession, with very low \( P/D\) signaling a high risk premium \(r^e\), said to themselves or their brokers, yes, this is a buying opportunity, stocks will likely bounce back. But my business is in danger of closing, my house might get foreclosed, I just can't take any risk right now.

In short, it is perfectly rational for investors to be more risk-averse, and demand a higher risk premium \(r^e\) in the bottom of recessions, and to hold stocks despite a low risk premium in quiet good times like right now. And this has nothing to do with the Fed, QE, or anything else.

John Campbell and I wrote a simple model of this phenomenon a long time ago, and I've reviewed it several times since, most recently here. Sorry for flogging the same ideas, but this possibility still hasn't made it to, say, the Fed-obsessed WSJ editorial pages, to say nothing of the Trump-obsessed pages at other outlets.

John and I tied risk aversion to consumption trends. If consumption is high relative to the recent past, in good times, you more willing to hold risk. If consumption is declining relative to the recent past, you get more scared. Lots of other mechanisms, including debt, work much the same way. If you don't like the precise model, consumption relative to recent past is a good general business cycle indicator.

Let's look historically. Here is consumption less a moving average (I used \(x_t = \sum_{j=0}^\infty 0.9^j c_{t-j})\), plotted with the log of the price/dividend ratio. The two series have different scales. The point is to see the correlation.

The pattern is longstanding. In good times, when consumption rises relative to recent past, stock valuations go up. In bad times, such as the great recession, consumption falls and so do stock valuations. People are scared. The same pattern happens regularly in the past.

The two lines drift apart, but as we saw above real interest rates account for that. Then the business-cycle related risk premium here accounts for the rises and dips.

And, if I may belabor the point, there was no QE, zero interest rates, and so forth going on in all these past instances when we see exactly the same pattern. Higher real interest rates are a regular, simple, utterly normal part of expansions, and lower risk premiums are a regular, simple, utterly normal part of expansions.

I was interested to read Tyler Cowen at Bloomberg back in to this view, based entirely on intuition:

This view should not necessarily make you sleep at night however. It means that a downturn will be accompanied by higher risk aversion again, and not only will dividends fall, prices will fall further. Moreover, historically, asset price falls have been preceded by periods of higher volatility. Alas, many periods of higher volatility have just faded away, so it's a warning sign not a signal. Sure, this mechanism means they will bounce back, but if you are clairvoyant enough to see it coming it will be better to avoid the fall! If not, well, be read to buy when everyone else is scared -- if you are one of the lucky few who can afford not to be scared.

The VIX, volatility, technical factors

There is another kind of ``discount factor variation,'' including 1987 and the flash crash. Sometimes the machinery of markets gets in the way, and prices fall more than they should. They quickly bounce back. If you can buy at the bottom you can make a fortune, but the prices fell precisely because it's hard to buy.

There were scattered report on Monday of hours long delays for retail customers to trade. (Can't find link.) But I do not get a sense this was a big clog in the markets. I would be curious to hear from people closer to markets.

The bigger news is the return of volatility -- big daily changes. To put this in historical perspective, here are two plots

The surprise, really, is just how low low volatility had become. Historically the stock market index has had a volatility around 15-20% per year -- a typical year saw a 15-20% change, and a typical day saw a \(15-20 / \sqrt{250} \approx \) one percent change. But, as you see in the top graph, volatility also declines in the late summer of the business cycle. Volatility has many occasional little eruptions, typically around price drops, and then washes away. Except when volatility rises in advance of the next recession and market decline. Which is this? I wish I knew.

Volatility is not about "fear" nor is it about "uncertainty." Volatility occurs when options change quickly. Constant bad news or good news just leads to constantly low or high prices. This is a sign of a time when either a lot of real information is hitting the market, or a lot of people are trying to process what's going on ahead of everyone else.

The "VIX bust" is hot in the news. A lot of people bet that the graph you saw above would not rise. To be ``short volatility'' means basically that you write insurance to people who worry about markets going down, (volatility is a big part of the value of put options) and you write insurance to people who are worried about events like right now in which markets start to move a lot. Hello, when you write insurance, occasionally you have to pay up.

As the graphs make clear, writing volatility insurance, or betting that volatility will continue to go down, is like writing earthquake insurance. Not much happens for many years in a row, and you can post nice profits. Then it jumps and you lose big time. Anyone who did this based just on historical returns is now crying the tears of the greedy neophyte. But they have lots of company. Back in the 1990s, Long Term Capital Management went under, basically for betting that similar looking graphs would continue to go down.

Well, if after all these years people are at it, P.T. Barnum had a good word for them. But did this have something to do with the stock market crash? How Bets Against Volatility Fed the Stock Market Rout in WSJ is an example of this train of thought.

On first glance, sure, a lot of people lost a ton of money, and then sold out other risky positions. But Econ 101: for every buyer there is a seller. Derivatives contracts are pure cases of this fact -- the net supply really is zero, for everybody who lost a dollar shorting VIX somebody else made a dollar buying it.

To get a story like this to go you need all sorts of market discombobulations. Somehow the people who lost money must be more important to markets than the people who made money. This can happen -- if a bunch of traders in a complex obscure security all lose money, and all try to sell, there is nobody to buy. But I don't really see that case here, and stocks are not a complex obscure security.

A trader friend also tells me that he has seen lots of people stop hedging -- so sure low volatility would continue that they don't cover the downside. He said many have lost a ton, and now are frantically selling to cover their positions. Such price pressure can have short run impacts, but does not last long.

Inflation and real interest rates

So we're back at hints of higher long-term real interest rates as the main likely culprit behind this week's decline and gyrations.

Here too most of the stories don't make much sense. Inflation per se should not make much difference. If expected inflation rises, interest rates rise, but real interest rates are unaffected. Inflation may make the Fed act more quickly, but there is not much correlation between what the Fed does with short term rates and the behavior of 10 year or more rates that matter to the stock market -- or to corporate investment.

Yes, there is some correlation -- especially at the end of expansions, short and long rates rise together. But the correlation is a whole lot less than the usual Wizard of Oz behind the curtain stories. And even the Fed cannot move real rates for very long. There is a good chicken-and-egg question whether the Fed can hold short rates down for long when long rates want to rise. The Fed pretty much has to jump in front of the parade and pretend to lead it.

Inflation does seem finally to be rising. The fact that higher rates are associated with the dollar falling suggests that a lot of the higher rates are due to inflation, and TIPs have not moved (top graph.)

So, the question before us is, are long-term real rates finally rising -- back to something like the historical norm that held for centuries, and if so why?

The good story is that we are entering a period of higher growth. Depending on your partisan tastes, point to tax cuts and deregulation, or state that Obama medicine is finally kicking in. This would raise real growth, with \(\gamma>1\) lead to a small stock price decline, but higher stock returns and bond returns going forward.

There is a bad story too. Having passed a tax cut that left untouched will lead to trillion-dollar deficits, Congressional leaders just agreed to $300 billion more spending. The Ryan plan that tax cuts would be followed by entitlement reform may be evaporating. Publicly held debt is $20 trillion. At some point bond markets say no, and real rates go up because the risk premium goes up. The US is in danger that higher interest rates mean higher interest costs on that debt, which means higher deficits, which means higher interest rates. $20 trillion times 5% interest = $1 trillion in interest costs.

The former leads to some inflation if you believe in the Phillips curve. The latter leads to stagflation in a tight fiscal moment.

Which is it? I don't know, I'm an academic not a trader.

One consolation of the stock market decline: I hope we don't have to hear how all the corporate tax cut did was to boost the stock market!

Well, two days ago this was going to be a short post responding to the WSJ's view that the Fed is behind it all, and Tyler's nice intuition. It got a bit out of hand, but I hope it's still interesting.

****

Data Update (Geeks only).

P/D isn't really "better" than P/E or other measures. A measure is what it is, you have to specify a question before there is an answer. Ideally, we want a measure that isolates expected returns, and tells us if prices are higher or lower given the level of expected dividends. So ideally, we would account for expected future dividends and the result would be a pure measure of expected returns (rational or not). P/D works pretty well that way because dividends are not very forecastable. Price divided by this year's dividends turns out to be a decent approximation to price divided by anyone's forecast of future dividends. But not perfect. P/E is less good that way because earnings bat about a bit more than dividends. For individual companies you can't use P/D, because so many of them do not pay dividends. Following Fama and French, the ratio of market value to book value is better there, because book value is usually positive, or not so frequently zero.

I use the CRSP definitions. I start from the CRSP return with and without dividends and infer the dividend yield. ''Dividends" here includes not only cash dividends but all cash payments to shareholders. So, if your small company gets bought by Google, and the shareholders get cash, that is a "dividend" payout. I suspect this accounts for the difference noted by WC Varones below. As others point out, earnings has all sorts of measurement issues, and also does not control for leverage.

Dividends are very seasonal, so you can't divide price by this month's dividends or you get a lot of noise. I use the last year's worth of dividends, brought forward by reinvesting them. This introduces some "return" into the dividend series. If you just sum dividends, though, identities like \(R_{t+1} = (P_{t+1}+D_{t+1})/P_t \) no longer hold in your annual data.

x = load('crsp_nyse_new_2018.txt');

caldt = x(:,1);

totval = x(:,2);

usdval = x(:,3);

sprtrn = x(:,4);

spindx = x(:,5);

vwretd = x(:,6);

vwretx = x(:,7);

[yr,mo,day,crsp_date_number] = decode_date(caldt);

T = size(vwretd,1);

vwretda = (1+vwretd(1:T-11)).*(1+vwretd(2:T-10)).*(1+vwretd(3:T-9)).*...

(1+vwretd(4:T-8)).*(1+vwretd(5:T-7)).*(1+vwretd(6:T-6)).*...

(1+vwretd(7:T-5)).*(1+vwretd(8:T-4)).*(1+vwretd(9:T-3)).*...

(1+vwretd(10:T-2)).*(1+vwretd(11:T-1)).*(1+vwretd(12:T));

vwretxa = (1+vwretx(1:T-11)).*(1+vwretx(2:T-10)).*(1+vwretx(3:T-9)).*...

(1+vwretx(4:T-8)).*(1+vwretx(5:T-7)).*(1+vwretx(6:T-6)).*...

(1+vwretx(7:T-5)).*(1+vwretx(8:T-4)).*(1+vwretx(9:T-3)).*...

(1+vwretx(10:T-2)).*(1+vwretx(11:T-1)).*(1+vwretx(12:T));

vwdp = vwretda./vwretxa-1; %D_t+1/P_t+1 = [(P_t+1+D_t+1)/P_t] / [P_t+1/P_t] -1;

vwdda = vwdp(13:end)./vwdp(1:end-12).*vwretxa(13:end); % D_t+1/D_t = D_t+1/P_t+1 / D_t/P_t * P_t+1/P_t

vwdda = [ones(23,1)*NaN; vwdda];

cumval = cumprod(1+vwretd);

vwdp = [ ones(11,1)*NaN; vwdp]; % keep length of series the same

I get stock data from CRSP via WRDS. This is the NYSE only. I can't post the full data, as it belongs to CRSP. Here is an excerpt that will let you calculate the last year, and check that things are right if you download the whole thing.

%crsp_nyse_new_2018.txt

% caldt totval usdval sprtrn spindx vwretd vwretx

19260130 27624240.80 27412916.20 0.022472 12.74 0.000561 -0.001395

19260227 26752064.10 27600952.10 -0.043956 12.18 -0.033046 -0.036587

19260331 25083173.40 26683758.10 -0.059113 11.46 -0.064002 -0.070021

19260430 25886743.80 24899755.60 0.022688 11.72 0.037019 0.034031

...

20160129 17059005700.00 17976992500.00 -0.050735 1940.24 -0.050111 -0.051700

20160229 16986848800.00 17001893900.00 -0.004128 1932.23 0.005104 0.002251

20160331 18122913200.00 16951468600.00 0.065991 2059.74 0.072190 0.069562

20160429 18503144900.00 18082712100.00 0.002699 2065.30 0.023324 0.021716

20160531 18479138100.00 18410229900.00 0.015329 2096.96 0.006124 0.003392

20160630 18613173100.00 18422135300.00 0.000906 2098.86 0.011175 0.008957

20160729 19054705700.00 18557630600.00 0.035610 2173.60 0.028433 0.026872

20160831 18993464300.00 19049575300.00 -0.001219 2170.95 0.000196 -0.002532

20160930 18829544800.00 18880924600.00 -0.001234 2168.27 -0.003876 -0.005878

20161031 18404742600.00 18802632900.00 -0.019426 2126.15 -0.021331 -0.022944

20161130 19220882900.00 18383296300.00 0.034174 2198.81 0.048548 0.045701

20161230 19568491300.00 19178151000.00 0.018201 2238.83 0.021566 0.019486

20170131 19824534000.00 19526674900.00 0.017884 2278.87 0.014007 0.012623

20170228 20355248600.00 19781803200.00 0.037198 2363.64 0.031422 0.028905

20170331 20237616500.00 20334429600.00 -0.000389 2362.72 -0.003961 -0.006103

20170428 20286715000.00 20194157100.00 0.009091 2384.20 0.003950 0.002468

20170531 20299003900.00 20276905500.00 0.011576 2411.80 0.002199 -0.000507

20170630 20602218600.00 20256933000.00 0.004814 2423.41 0.018204 0.016235

20170731 20747539100.00 20488018000.00 0.019349 2470.30 0.015290 0.013394

20170831 20593088100.00 20742392900.00 0.000546 2471.65 -0.005133 -0.007874

20170929 21147810200.00 20381001300.00 0.019303 2519.36 0.030435 0.028662

20171031 21343546700.00 21130998500.00 0.022188 2575.26 0.011831 0.010360

20171130 21904734200.00 21302790800.00 0.028083 2647.58 0.030537 0.027670

20171229 22016063100.00 21683038400.00 0.009832 2673.61 0.015914 0.014117

(Note: This post has equations, graphs and quotes that tend to get mangled when it gets picked up. If it's mangled, come back to the original here.)

Why do prices fall?

Stock prices fall when there is bad news about future profits, or when the discount rate rises.

The discount rate is the rate investors require, looking forward, to get them to buy stocks. If people require a better rate of return, with no change in their expected cashflows, prices drop.

Stop and think about that a second, as it's counterintuitive. Yes, the only way to get a better return out of the same profits or dividends is for today's price to drop.

Another way to think about it: Suppose all of a sudden there are good profitable opportunities for your money -- bond interest rates rise, or it's a good time to take money out of markets and invest in your company. Well, people will try to move money to those alternatives. But the stock market is a hot potato; someone has to hold the stocks. So stock prices must decline until the rate of return going forward matches the other attractions on a risk-adjusted basis. Good news about returns going forward is bad news about a downward jump in stock prices.

Bad news about cashflows is, well, bad news. The dashed line shifts down. Your stocks are not going to pay off as well as before. Higher required returns are neutral, really, for long-term investors. The price drops today, but the higher returns mean the price will slowly recover, just as long-term government bonds do.

So is this a moment of bad cashflow news or higher discount rate? Most commentary suggests it's not bad news about cashflows. The economy seems finally to be growing, and there isn't anything like a brewing subprime or other problem, as there was in 2007. Maybe we don't know about it, but one certainly doesn't read about it.

So let's think about discount rates. Why might investors require a higher return on stocks? Is it interest rates, a risk premium, and is the Fed behind it all?

Where are we?

Are we in a "bubble'' that is about to pop? Let's start by reviewing some facts. Here is the cumulative return on the NYSE since 1990. (This is the CRSP NYSE. Sadly the data stops 12/31/2017 so I don't show the recent drop. The larger index including NASDAQ shows a larger rise and fall in the tech boom and bust, but is otherwise about the same.)

|

| Cumulative return NYSE since 1990. Source CRSP |

Update: Thanks to Torsten Slok at DB the last year follows. His point, it's sharp but not all that big.

Next, look at the price-dividend ratio. (For a variety of reasons this is a better valuation measure than the commonly used price earnings ratio. This (CRSP) measure of dividends includes all cash payment to shareholders. No, repurchases don't cause a problem.)

|

| Price / dividend ratio, NYSE. Source CRSP |

Where is the booming stock market? Stock prices relative to dividends have not grown at all since the end of the recession. Well, evidently, dividends have been rising just as fast as prices in the current expansion -- which again weren't rising all that fast anyway. So the main reason stock prices are high is that dividends are high, and people expect that slow growth to continue.

So here we were before the recent drop. Are prices too high? Well, not as much as in 1999 for sure! But P/D is a lot higher than historical norms. Is this the beginning of a drop back to historic levels like 30, or even 20? Or is this a new normal? There is way too much commentary lately that whatever we remember from 20 years ago was "normal" and that things have to go back to that. Not without a reason.

Interest rates and stock prices

To think about this question we need some basics of what determines price-dividend ratios. Over long time periods, the return you get on stocks is the dividend yield -- how many dividends they pay per dollar invested plus the growth in dividends. Over short time periods you also get price appreciation per dividend, but over long time periods, the ratio of price to dividends comes back and price growth is the same as dividend growth. In sum,

return = dividend yield + growth rate

\[ r = \frac{D}{P} + g \]This is also where price comes from. The price you're willing to pay depends on the expected return going forward, and expected dividend growth (Prices are high relative to current dividends if people expect a lot more dividends in the future.)\[ \frac{D}{P} = r - g = r^l + r^e - g \]\[ \frac{P}{D} =\frac{1}{r - g} =\frac{1}{ r^l + r^e - g} \] Here I broke apart the expected return into components. First, the expected return on stocks is equal to the long-term real risk-free rate \(r^l\) plus the risk premium \(r^e\). This is just a definition -- the risk premium is \(r^e=r-r^l\).So, looked at either as D/P or P/D, we now have the tools to think about what pushes stock prices around.

(There is nothing inherently ``rational'' or ``efficient markets'' about this. Behavioral finance just says the expectations are wrong, for example that people think \(g\) is big when in fact \(r\) is small.)

Stock prices are very sensitive to real interest rates, risk premiums, and growth expectations. At our current P/D of 40, for example, this means \(r-g=1/40=0.025\) or 2.5%. Just half a percent change in expected return or growth rate, \(r-g=0.02\) would mean \(P/D=1/0.02=50\), a 25% rise in stock prices. Conversely, a half percent rise in real interest rates would mean \(r-g=0.03\), a decline to \(P/D=33\) a 16.7% fall. No wonder stocks are (usually) volatile!

Now, to what's going on? If we take growth rate expectations off the table, then stock prices are moving because of changes in interest rates. And small interest rate changes do indeed imply big stock valuation changes -- though, again, take heart because it means the rate of return is higher, as in the first picture.

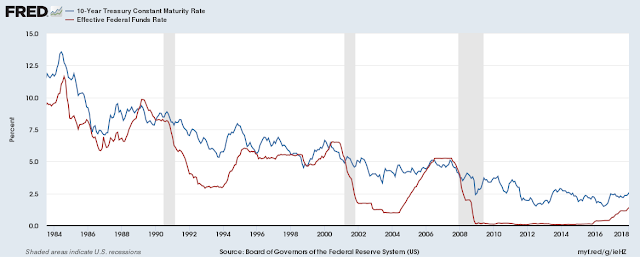

Does this relationship hold historically? Here is the D/P ratio (P/D upside down) and a measure of long-term real interest rates.

|

| NYSE D/P, Cleveland Fed 10 Year real rate, and 10 year TIPS |

(The problem with 10 year real rates is knowing what 10 year expected inflation is, given that we did not have TIPS. There are lots of other problems too, such as unwinding the liquidity premium in government bonds. Here I used the Cleveland Fed's real rate model, which is in part based on survey expectations. I added the 10 year TIPS yield where we have it to confirm the general pattern of the Cleveland Fed's calculation.)

This is a remarkable graph: The entire rise in valuations from 1980 to 2008 corresponds exactly to the decline in real interest rates.

By this measure, the decline in real rates was huge, from 7% to essentially 0%. Plug that in to \(P/D=1/(r-g)\) and we're done. Stock prices are exactly where they should be.

In fact, by this measure, stock prices are too low. In 2008, real rates kept right on trundling down another two percentage points, but the dividend yield stabilized.

Well, I was careful to say "corresponds to" not "caused by" for a reason. The risk premium and growth expectations changed as well. Arguably the move to a low-growth economy starting in 2000, cutting one to two percentage points off \(g\), offset the decline in real rate. Or perhaps the risk premium isn't as low as we think it is. This isn't just waffling -- the relationship is basically an identity. One of those options must be true. If the dividend yield is 2.5%, and the real interest rate is 0%, then \(r^e-g\) is 2.5%, and has grown since 2000. Either the risk premium has grown 2.5% -- so much for the ``low risk premium'' -- or growth expectations have fallen 2.5%. Or the long-term real rate is profoundly mismeasured here.

More on all this in a minute. But the graph reminds us 1) Real rates have come down a lot, and 2) persistent changes in real rates really are an important part of stock market valuations. Oh, and they have nothing to do with ``risk appetite'' and all that other blather. Stocks are valued like bonds plus risk. We are noticing here that the bond-like component got much more valuable. That alone, not the risk component or the growth component, accounts for two decades of huge price rises.

This actually updates significantly some of my own work, and the asset pricing consensus. The great question why do price-dividend ratios vary so much occupied us a lot in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including myself, John Campbell, Bob Shiller, Gene Fama and Ken French. The rough answer we came to -- pretty much all variation in D/P or P/D comes down to variation in risk premiums, the \(r^e=r-r^l\) term. The underlying fact is that times of high P/D are not reliably followed by higher dividend growth (Shiller), and they are reliably followed by low excess returns (Fama and French). If you add it up, the risk premium effect neatly accounts for all the variation in P/D (Campbell and Shiller, me).

Well, in the data up to 1990, we didn't see much persistent variation in real rates of interest, and what we did see was not correlated well with stock prices. Well, that was 1990, and now is now. This graph suggests that in fact a lot of the recent variation in P/D corresponds to lower real interest rates. Also, it's the low frequency, decade to decade movement in P/D that is not well accounted for by any models. An academic version of this observation needs to be written.

Practical bottom line: The stories that the recent stock price decline comes from rising long-term real interest rates make sense. They might be wrong, but they make sense. That's saying a lot more than most of the other stories being bandied around right now.

Interest rates, growth, stock prices, and the Fed.

The story is not that easy however. We have to think about real interest rates \(r\) and growth \(g\) together. And there is this puzzle to answer -- how can it be that good news about the economy sends the market down? If \(P/D=1/(r-g)\) more \(g\) should raise \(P\), no? It should shift up the dashed line in my first graph?

No. We have to think about where real interest rates come from. One of the most basic relationships in economics is that higher growth means higher real interest rates. If everyone will be richer in the future -- growth -- they need an incentive to save and not blow it all today. And growth means a higher marginal product of capital, and hence higher interest rates. As a simple equation, \[ \text{real rate} = \gamma g \]where \(\gamma\) is a parameter, usually between about 1/2 and 2, and get ready for a bar fight at the AEA convention over just what value to use. 1% higher growth means about a half percent to two percent higher real interest rate.

(There is a second term too, important in understanding things like the financial crisis. More uncertainty means lower interest rates. Not today.)

If \(\gamma=1\), if one percent growth means one percent higher real interest rates, then higher growth has no effect at all on stock prices or price dividend ratios. (\(D/P = r^l + r^e - g.\) Raise \(r^l\) and \(g\) by the same amount.) If, as I think is more likely right in this case, \(\gamma>1\), then higher growth lowers stock prices. Yes. Higher growth means a higher discount rate as well as more dividends. The discount rate effect can overwhelm the cashflow effect.

This has nothing to do with the Fed. There is a natural human tendency to look for Agency, for some man or woman behind the curtain pulling all the strings, and these days that means the Fed. For example, the WSJ Editorial on stocks:

"The paradox of the equity-market correction is that it’s taking place even as the real economy looks stronger than it’s been since at least 2005 and maybe 1999. "

"So why are stocks falling amid all the good news? The best answer we’ve heard is that stocks are reflecting a return to volatility and risk after years of the Fed’s financial repression. With its quantitative easing bond purchases, the Fed has for a decade suppressed market price signals in bonds."

"Investors may finally be figuring out that the global quantitative-easing monetary party is ending."Look back at my graph. Real interest rates have been on a slow downward trend since 1980. That trend is unbroken since 2008. There is not a whiff that QE or anything else has budged that trend. (Lots of good graphs on this point in 8 heresies of monetary policy here. ) If the Fed has anything to do with it, it is the slow victory over inflation expectations, not QE and a lot of talk.

Yes, the papers like to say that higher growth will induce the Fed to raise rates. The Fed can put a finger in this dike for a bit if they want to, but even the Fed cannot long fight the positive or negative relationship between real growth and real interest rates.

So it makes perfect sense, at least as a logical possibility, that more growth lowers stock prices! Again, this is like my lower line in the first picture -- and actually a bit better because we also raise the terminal point. If this is what happened, well, regret that you didn't see it happening and stay out during the dip, but be reassured the market will make it back.

Risk premiums

What about the ``unusually low risk premium''? Aren't the Fed's ``massive QE and abnormally low interest rates distorting risk premiums and causing asset price bubbles?'' (The best definition of ``bubble'' I can muster is a risk premium that is too low, distorted somehow.)

Here is the contrary view. We are at the late summer of the business cycle. The economy is relatively healthy, at least if you're a stock market investor. (Many of these own companies.) Economic volatility is still at an all time low. Bonds are still giving pretty atrocious real returns. Yeah, stocks look pretty healthily priced -- as you contemplate your \(P/D = 1/(r^l + r^e - g)\) it looks like the extra return from stocks \(r^e\) is pretty low. But what else are you going to do with the money? You can afford a little risk. Contrariwise, the same investors in the bottom of the great recession, with very low \( P/D\) signaling a high risk premium \(r^e\), said to themselves or their brokers, yes, this is a buying opportunity, stocks will likely bounce back. But my business is in danger of closing, my house might get foreclosed, I just can't take any risk right now.

In short, it is perfectly rational for investors to be more risk-averse, and demand a higher risk premium \(r^e\) in the bottom of recessions, and to hold stocks despite a low risk premium in quiet good times like right now. And this has nothing to do with the Fed, QE, or anything else.

John Campbell and I wrote a simple model of this phenomenon a long time ago, and I've reviewed it several times since, most recently here. Sorry for flogging the same ideas, but this possibility still hasn't made it to, say, the Fed-obsessed WSJ editorial pages, to say nothing of the Trump-obsessed pages at other outlets.

John and I tied risk aversion to consumption trends. If consumption is high relative to the recent past, in good times, you more willing to hold risk. If consumption is declining relative to the recent past, you get more scared. Lots of other mechanisms, including debt, work much the same way. If you don't like the precise model, consumption relative to recent past is a good general business cycle indicator.

Let's look historically. Here is consumption less a moving average (I used \(x_t = \sum_{j=0}^\infty 0.9^j c_{t-j})\), plotted with the log of the price/dividend ratio. The two series have different scales. The point is to see the correlation.

|

| Consumption minus a moving average, and log P/D on NYSE. |

The pattern is longstanding. In good times, when consumption rises relative to recent past, stock valuations go up. In bad times, such as the great recession, consumption falls and so do stock valuations. People are scared. The same pattern happens regularly in the past.

The two lines drift apart, but as we saw above real interest rates account for that. Then the business-cycle related risk premium here accounts for the rises and dips.

And, if I may belabor the point, there was no QE, zero interest rates, and so forth going on in all these past instances when we see exactly the same pattern. Higher real interest rates are a regular, simple, utterly normal part of expansions, and lower risk premiums are a regular, simple, utterly normal part of expansions.

I was interested to read Tyler Cowen at Bloomberg back in to this view, based entirely on intuition:

In a volatile and uncertain time politically, we have observed sky-high prices for blue-chip U.S. equities. Other asset prices also seem to be remarkably high: home values and rentals in many of the world’s top-tier cities, negative real rates and sometimes negative nominal rates on the safest government securities, and the formerly skyrocketing and still quite high price of Bitcoin and other crypto-assets.

Might all of those somewhat unusual asset prices be part of a common pattern? Consider that over the past few decades there has been a remarkable increase of wealth in the world, most of all in the emerging economies. Say you hold enough wealth to invest: What are your options?

In relative terms, the high-quality, highly liquid blue-chip assets will become expensive. So we end up with especially high price-to-earnings ratios and consistently negative real yields on safe government securities. Those price patterns don’t have to be bubbles. If this state of affairs persists, with a shortage of safe investment opportunities, those prices can stay high for a long time. They may go up further yet.

These high asset prices do reflect a reality of wealth creation. They are broadly bullish at the global scale, but they don’t have to demonstrate much if any good news about those assets per se. Rather there is an imbalance between world wealth and safe ways of transferring that wealth into the future

To sum this all up in a single nerdy finance sentence, in a world where wealth creation has outraced the evolution of good institutions, the risk premium may be more important than you think.

Except for this business about "shortage of safe assets," that's pretty much the intuition. (Tyler: all assets are in fixed supply in the short run. Prices adjust. This isn't really a ``shortage.'') The point that high valuations extend to homes, bonds, bitcoins, and global stocks is a good indicator that the phenomenon is generalized risk aversion rather than something specific to one market or economy.

This view should not necessarily make you sleep at night however. It means that a downturn will be accompanied by higher risk aversion again, and not only will dividends fall, prices will fall further. Moreover, historically, asset price falls have been preceded by periods of higher volatility. Alas, many periods of higher volatility have just faded away, so it's a warning sign not a signal. Sure, this mechanism means they will bounce back, but if you are clairvoyant enough to see it coming it will be better to avoid the fall! If not, well, be read to buy when everyone else is scared -- if you are one of the lucky few who can afford not to be scared.

The VIX, volatility, technical factors

There is another kind of ``discount factor variation,'' including 1987 and the flash crash. Sometimes the machinery of markets gets in the way, and prices fall more than they should. They quickly bounce back. If you can buy at the bottom you can make a fortune, but the prices fell precisely because it's hard to buy.

There were scattered report on Monday of hours long delays for retail customers to trade. (Can't find link.) But I do not get a sense this was a big clog in the markets. I would be curious to hear from people closer to markets.

The bigger news is the return of volatility -- big daily changes. To put this in historical perspective, here are two plots

The surprise, really, is just how low low volatility had become. Historically the stock market index has had a volatility around 15-20% per year -- a typical year saw a 15-20% change, and a typical day saw a \(15-20 / \sqrt{250} \approx \) one percent change. But, as you see in the top graph, volatility also declines in the late summer of the business cycle. Volatility has many occasional little eruptions, typically around price drops, and then washes away. Except when volatility rises in advance of the next recession and market decline. Which is this? I wish I knew.

Volatility is not about "fear" nor is it about "uncertainty." Volatility occurs when options change quickly. Constant bad news or good news just leads to constantly low or high prices. This is a sign of a time when either a lot of real information is hitting the market, or a lot of people are trying to process what's going on ahead of everyone else.

The "VIX bust" is hot in the news. A lot of people bet that the graph you saw above would not rise. To be ``short volatility'' means basically that you write insurance to people who worry about markets going down, (volatility is a big part of the value of put options) and you write insurance to people who are worried about events like right now in which markets start to move a lot. Hello, when you write insurance, occasionally you have to pay up.

As the graphs make clear, writing volatility insurance, or betting that volatility will continue to go down, is like writing earthquake insurance. Not much happens for many years in a row, and you can post nice profits. Then it jumps and you lose big time. Anyone who did this based just on historical returns is now crying the tears of the greedy neophyte. But they have lots of company. Back in the 1990s, Long Term Capital Management went under, basically for betting that similar looking graphs would continue to go down.

Well, if after all these years people are at it, P.T. Barnum had a good word for them. But did this have something to do with the stock market crash? How Bets Against Volatility Fed the Stock Market Rout in WSJ is an example of this train of thought.

On first glance, sure, a lot of people lost a ton of money, and then sold out other risky positions. But Econ 101: for every buyer there is a seller. Derivatives contracts are pure cases of this fact -- the net supply really is zero, for everybody who lost a dollar shorting VIX somebody else made a dollar buying it.

To get a story like this to go you need all sorts of market discombobulations. Somehow the people who lost money must be more important to markets than the people who made money. This can happen -- if a bunch of traders in a complex obscure security all lose money, and all try to sell, there is nobody to buy. But I don't really see that case here, and stocks are not a complex obscure security.

A trader friend also tells me that he has seen lots of people stop hedging -- so sure low volatility would continue that they don't cover the downside. He said many have lost a ton, and now are frantically selling to cover their positions. Such price pressure can have short run impacts, but does not last long.

Inflation and real interest rates

So we're back at hints of higher long-term real interest rates as the main likely culprit behind this week's decline and gyrations.

Here too most of the stories don't make much sense. Inflation per se should not make much difference. If expected inflation rises, interest rates rise, but real interest rates are unaffected. Inflation may make the Fed act more quickly, but there is not much correlation between what the Fed does with short term rates and the behavior of 10 year or more rates that matter to the stock market -- or to corporate investment.

Yes, there is some correlation -- especially at the end of expansions, short and long rates rise together. But the correlation is a whole lot less than the usual Wizard of Oz behind the curtain stories. And even the Fed cannot move real rates for very long. There is a good chicken-and-egg question whether the Fed can hold short rates down for long when long rates want to rise. The Fed pretty much has to jump in front of the parade and pretend to lead it.

Inflation does seem finally to be rising. The fact that higher rates are associated with the dollar falling suggests that a lot of the higher rates are due to inflation, and TIPs have not moved (top graph.)

So, the question before us is, are long-term real rates finally rising -- back to something like the historical norm that held for centuries, and if so why?

The good story is that we are entering a period of higher growth. Depending on your partisan tastes, point to tax cuts and deregulation, or state that Obama medicine is finally kicking in. This would raise real growth, with \(\gamma>1\) lead to a small stock price decline, but higher stock returns and bond returns going forward.

There is a bad story too. Having passed a tax cut that left untouched will lead to trillion-dollar deficits, Congressional leaders just agreed to $300 billion more spending. The Ryan plan that tax cuts would be followed by entitlement reform may be evaporating. Publicly held debt is $20 trillion. At some point bond markets say no, and real rates go up because the risk premium goes up. The US is in danger that higher interest rates mean higher interest costs on that debt, which means higher deficits, which means higher interest rates. $20 trillion times 5% interest = $1 trillion in interest costs.

The former leads to some inflation if you believe in the Phillips curve. The latter leads to stagflation in a tight fiscal moment.

Which is it? I don't know, I'm an academic not a trader.

One consolation of the stock market decline: I hope we don't have to hear how all the corporate tax cut did was to boost the stock market!

Well, two days ago this was going to be a short post responding to the WSJ's view that the Fed is behind it all, and Tyler's nice intuition. It got a bit out of hand, but I hope it's still interesting.

****

Data Update (Geeks only).

P/D isn't really "better" than P/E or other measures. A measure is what it is, you have to specify a question before there is an answer. Ideally, we want a measure that isolates expected returns, and tells us if prices are higher or lower given the level of expected dividends. So ideally, we would account for expected future dividends and the result would be a pure measure of expected returns (rational or not). P/D works pretty well that way because dividends are not very forecastable. Price divided by this year's dividends turns out to be a decent approximation to price divided by anyone's forecast of future dividends. But not perfect. P/E is less good that way because earnings bat about a bit more than dividends. For individual companies you can't use P/D, because so many of them do not pay dividends. Following Fama and French, the ratio of market value to book value is better there, because book value is usually positive, or not so frequently zero.

I use the CRSP definitions. I start from the CRSP return with and without dividends and infer the dividend yield. ''Dividends" here includes not only cash dividends but all cash payments to shareholders. So, if your small company gets bought by Google, and the shareholders get cash, that is a "dividend" payout. I suspect this accounts for the difference noted by WC Varones below. As others point out, earnings has all sorts of measurement issues, and also does not control for leverage.

Dividends are very seasonal, so you can't divide price by this month's dividends or you get a lot of noise. I use the last year's worth of dividends, brought forward by reinvesting them. This introduces some "return" into the dividend series. If you just sum dividends, though, identities like \(R_{t+1} = (P_{t+1}+D_{t+1})/P_t \) no longer hold in your annual data.

x = load('crsp_nyse_new_2018.txt');

caldt = x(:,1);

totval = x(:,2);

usdval = x(:,3);

sprtrn = x(:,4);

spindx = x(:,5);

vwretd = x(:,6);

vwretx = x(:,7);

[yr,mo,day,crsp_date_number] = decode_date(caldt);

T = size(vwretd,1);

vwretda = (1+vwretd(1:T-11)).*(1+vwretd(2:T-10)).*(1+vwretd(3:T-9)).*...

(1+vwretd(4:T-8)).*(1+vwretd(5:T-7)).*(1+vwretd(6:T-6)).*...

(1+vwretd(7:T-5)).*(1+vwretd(8:T-4)).*(1+vwretd(9:T-3)).*...

(1+vwretd(10:T-2)).*(1+vwretd(11:T-1)).*(1+vwretd(12:T));

vwretxa = (1+vwretx(1:T-11)).*(1+vwretx(2:T-10)).*(1+vwretx(3:T-9)).*...

(1+vwretx(4:T-8)).*(1+vwretx(5:T-7)).*(1+vwretx(6:T-6)).*...

(1+vwretx(7:T-5)).*(1+vwretx(8:T-4)).*(1+vwretx(9:T-3)).*...

(1+vwretx(10:T-2)).*(1+vwretx(11:T-1)).*(1+vwretx(12:T));

vwdp = vwretda./vwretxa-1; %D_t+1/P_t+1 = [(P_t+1+D_t+1)/P_t] / [P_t+1/P_t] -1;

vwdda = vwdp(13:end)./vwdp(1:end-12).*vwretxa(13:end); % D_t+1/D_t = D_t+1/P_t+1 / D_t/P_t * P_t+1/P_t

vwdda = [ones(23,1)*NaN; vwdda];

cumval = cumprod(1+vwretd);

vwdp = [ ones(11,1)*NaN; vwdp]; % keep length of series the same

I get stock data from CRSP via WRDS. This is the NYSE only. I can't post the full data, as it belongs to CRSP. Here is an excerpt that will let you calculate the last year, and check that things are right if you download the whole thing.

%crsp_nyse_new_2018.txt

% caldt totval usdval sprtrn spindx vwretd vwretx

19260130 27624240.80 27412916.20 0.022472 12.74 0.000561 -0.001395

19260227 26752064.10 27600952.10 -0.043956 12.18 -0.033046 -0.036587

19260331 25083173.40 26683758.10 -0.059113 11.46 -0.064002 -0.070021

19260430 25886743.80 24899755.60 0.022688 11.72 0.037019 0.034031

...

20160129 17059005700.00 17976992500.00 -0.050735 1940.24 -0.050111 -0.051700

20160229 16986848800.00 17001893900.00 -0.004128 1932.23 0.005104 0.002251

20160331 18122913200.00 16951468600.00 0.065991 2059.74 0.072190 0.069562

20160429 18503144900.00 18082712100.00 0.002699 2065.30 0.023324 0.021716

20160531 18479138100.00 18410229900.00 0.015329 2096.96 0.006124 0.003392

20160630 18613173100.00 18422135300.00 0.000906 2098.86 0.011175 0.008957

20160729 19054705700.00 18557630600.00 0.035610 2173.60 0.028433 0.026872

20160831 18993464300.00 19049575300.00 -0.001219 2170.95 0.000196 -0.002532

20160930 18829544800.00 18880924600.00 -0.001234 2168.27 -0.003876 -0.005878

20161031 18404742600.00 18802632900.00 -0.019426 2126.15 -0.021331 -0.022944

20161130 19220882900.00 18383296300.00 0.034174 2198.81 0.048548 0.045701

20161230 19568491300.00 19178151000.00 0.018201 2238.83 0.021566 0.019486

20170131 19824534000.00 19526674900.00 0.017884 2278.87 0.014007 0.012623

20170228 20355248600.00 19781803200.00 0.037198 2363.64 0.031422 0.028905

20170331 20237616500.00 20334429600.00 -0.000389 2362.72 -0.003961 -0.006103

20170428 20286715000.00 20194157100.00 0.009091 2384.20 0.003950 0.002468

20170531 20299003900.00 20276905500.00 0.011576 2411.80 0.002199 -0.000507

20170630 20602218600.00 20256933000.00 0.004814 2423.41 0.018204 0.016235

20170731 20747539100.00 20488018000.00 0.019349 2470.30 0.015290 0.013394

20170831 20593088100.00 20742392900.00 0.000546 2471.65 -0.005133 -0.007874

20170929 21147810200.00 20381001300.00 0.019303 2519.36 0.030435 0.028662

20171031 21343546700.00 21130998500.00 0.022188 2575.26 0.011831 0.010360

20171130 21904734200.00 21302790800.00 0.028083 2647.58 0.030537 0.027670

20171229 22016063100.00 21683038400.00 0.009832 2673.61 0.015914 0.014117

If I screwed up, let me know and I'll fix it!

Truck automation

Two bits from Marginal Revolution on truck automation are so good they merit passing on here. Dan Hanson writes this amazing comment

The comment was on an earlier MR post covering Alexis Madrigal in the Atlantic on self-driving trucks. Automation in any industry reduces costs and increases quality. These mean the industry expands, so labor demand may even grow. Think of the computer you're reading this on. Labor gets to specialize at the things people are good at, which is higher productivity, and wages rise.

And I just googled "truck driver shortage" to get the latest media story to rediscover this fact. From NPR "Trucking Industry Struggles With Growing Driver Shortage",

(Of course we don't use the word "shortage" in economics unless there is a government-imposed price control. This just means wages will go up.)

Update: Thanks to the comment from Unknown below, here is the response from Tom T in MRs comments

I wonder how many of the people making predictions about the future of truck drivers have ever ridden with one to see what they do?

One of the big failings of high-level analyses of future trends is that in general they either ignore or seriously underestimate the complexity of the job at a detailed level. Lots of jobs look simple or rote from a think tank or government office, but turn out to be quite complex when you dive into the details.

For example, truck drivers don’t just drive trucks. They also secure loads, including determining what to load first and last and how to tie it all down securely. They act as agents for the trunking company. They verify that what they are picking up is what is on the manifest. They are the early warning system for vehicle maintenance. They deal with the government and others at weighing stations. When sleeping in the cab, they act as security for the load. If the vehicle breaks down, they set up road flares and contact authorities. If the vehicle doesn’t handle correctly, the driver has to stop and analyze what’s wrong – blown tire, shifting load, whatever.

In addition, many truckers are sole proprietors who own their own trucks. This means they also do all the bookwork, preventative maintenance, taxes, etc. These people have local knowledge that is not easily transferable. They know the quirks of the routes, they have relationships with customers, they learn how best to navigate through certain areas, they understand how to optimize by splitting loads or arranging for return loads at their destination, etc. They also learn which customers pay promptly, which ones provide their loads in a way that’s easy to get on the truck, which ones generally have their paperwork in order, etc. Loading docks are not all equal. Some are very ad-hoc and require serious judgement to be able to manoever large trucks around them. Never underestimate the importance of local knowledge.

... a fundamentally Hayekian insight: When it comes to large scale activities, nothing about change is easy, and top-down change generally fails...I would add silicon valley software companies, and media commentators to the think tanks and government offices, on the list of pundits that tend to denigrate the skill, knowledge and intelligence required of what are very wrongly call "low skilled" jobs. I note several times the "paperwork" required in trucking as well.

The comment was on an earlier MR post covering Alexis Madrigal in the Atlantic on self-driving trucks. Automation in any industry reduces costs and increases quality. These mean the industry expands, so labor demand may even grow. Think of the computer you're reading this on. Labor gets to specialize at the things people are good at, which is higher productivity, and wages rise.

Uber does not believe that self-driving trucks will be doing “dock to dock” runs for a very long time. They see a future in which self-driving trucks drive highway miles between what they call transfer hubs, where human drivers will take over for the last miles through complex urban and industrial terrain.And fill out that paperwork.

if the self-driving trucks are used far more efficiently, it would drive down the cost of freight, which would stimulate demand, leading to more business. And, if more freight is out on the roads, and humans are required to run it around local areas, then there will be a greater, not lesser, need for truck drivers.The article misses the second, more important effect. As low-cost trucking expands, other businesses that use trucks expand, and they hire people too.

And I just googled "truck driver shortage" to get the latest media story to rediscover this fact. From NPR "Trucking Industry Struggles With Growing Driver Shortage",

The trucking industry is facing a growing shortage of drivers that is pushing some retailers to delay nonessential shipments or pay high prices to get their goods delivered on time.

A report from the American Trucking Associations says more than 70 percent of goods consumed in the U.S. are moved by truck, but the industry needs to hire almost 900,000 more drivers to meet rising demand.It's a tough job. Young people aren't going in to it. There are competing opportunities. My last Uber driver just quit long-haul truck driving. He earns a bit less, but gets to see his family every night.

(Of course we don't use the word "shortage" in economics unless there is a government-imposed price control. This just means wages will go up.)

Update: Thanks to the comment from Unknown below, here is the response from Tom T in MRs comments

This comment reminds me of the guy in Office Space who ends up helplessly screaming at the downsizing consultants, “I have people skills!”

It’s trying way too hard. Sure, the truckers do all of these things. But is there any reason to think that the self-driving AI won’t be just as good, if not far better, at confirming that the load is secure, verifying the manifest, monitoring vehicle maintenance, and interfacing with the weigh station? Does anyone really think a computer can’t split loads and optimize returns? Even accepting the dubious premise that the poor driver is somehow providing effective security by sleeping in the cab in front of the load, the whole need for that sleep-time security disappears when the vehicle is self-driving and doesn’t have to sleep. Truckers who are self-employed and have to do bookwork, taxes, and customer relationships will have a lot more time to devote to that end of the operations if they don’t also have to drive the truck. Loading docks that are ad hoc will find themselves either standardizing or paying extra for failing to do so, like every other aspect of an industrial, computerized world.

I’ve been a litigator for 25 years. At one time, we saw our profession as so paper-based and quirky and fact-dependent that it would always be safe from automation. Sure enough, OCR text recognition, keyword searches, and predictive algorithms completely changed the economics of document review. No one is immune from automation.I heard somewhere, I forget where, the quip that the ones who really should fear automation are accountants, book keepers, and other fairly routine paperwork office workers. It sounds awfully sensible. Of course our government is pretty good at expanding the demand for paperwork!

Convexification and complication

From Richard Rubin at WSJ:

In economics we call this "convexification". There are lots of clever ways to draw lines through a stair step.

Of course, you can also just give $50,000 to charity in alternate years, and let the charity put it in the bank. Donor-advised funds are useful if you think your local charity's endowment investment policy isn't that smart. If they invest in obscure high-fee hedge funds and private equity deals and you'd rather they invested your money in transparent low-fee assets, then set up a donor-advised fund.

In a rare moment of sanity and good government from my ex-home state, Marc Levine, chairman of the Illinois state board of investment, pulled all of Illinois' pension assets out of high-fee obscure hedge funds.

Donor-advised funds are also a great way to give money to your favorite charity if you think their own investment

The article includes more clever advice:

It gets better though. Give a non-market asset to your favorite charity. You can see both you and the charity have every incentive to report fanciful values for the asset. If it's really worth $100, well, call it $200 for the IRS. The charity still gets $100 for free.

Now you can actually make money out of donations. Conservation easement syndications (here, here and most fun here are even better. Buy land cheap, declare a huge value, put the land in a conservation trust, promising not to build houses on it -- actual operating golf courses are ok, and too bad if sometime in 2050 building some houses is a good idea -- and deduct the high value against other income.

Obviously, I'm not such a fan. Even if you take a benign view -- the US likes to pass very high taxes for symbolic purposes, and then allows all sorts of shenanigans on the side so people don't actually have to pay the taxes -- much of the economic damage is done. Aside from the fact that marginal disincentives are high, the cost of all this stuff is not trivial either. From the first article

But even that is not the most annoying part. Now, on top of everything else, a wise taxpayer needs to set up a donor advised fund, sign a bunch of papers, and manage it each year. Already, perfectly normal citizens have to have trusts to manage estates, and hundreds of pages of tax forms each year. The needless complexity of life in the Republic of Paperwork is, to me, the most annoying part. We need a grand simplification of our public life. If this is what it leads to, the whole charitable deduction thing should get tossed overboard.

The new tax law’s treatment of deductions gives people more reasons to concentrate giving in certain years, both inside and outside donor-advised funds.

A donor-advised fund is an investment account held for charitable purposes. Donors take tax deductions when they put money in, then recommend grants to charities over time.

Mr. Young,...added $30,000 to a donor-advised fund run by the Los Altos Community Foundation. His plan: alternate years between taking the standard deduction and donating to his fund and claiming itemized deductions.How very clever. The tax law allows a $24,000 per year standard deduction. Arrange things so that in some years you have zero actual deductions, and get $24,000 free deduction. Pile all the real deductions into other years.

In economics we call this "convexification". There are lots of clever ways to draw lines through a stair step.

Of course, you can also just give $50,000 to charity in alternate years, and let the charity put it in the bank. Donor-advised funds are useful if you think your local charity's endowment investment policy isn't that smart. If they invest in obscure high-fee hedge funds and private equity deals and you'd rather they invested your money in transparent low-fee assets, then set up a donor-advised fund.

In a rare moment of sanity and good government from my ex-home state, Marc Levine, chairman of the Illinois state board of investment, pulled all of Illinois' pension assets out of high-fee obscure hedge funds.

Industry “experts” suggested we keep these investments to diversify our holdings and reduce overall risk. Yet we already owned bonds for that purpose. Our Procter & Gamble bonds made sense to us. I’m pretty sure my children will brush their teeth tonight. But I don’t have a clue about that long-lumber, short-sugar trade.

Did anyone at the table really understand what these hedge funds were doing? Should we be putting the retirement funds of Illinois state employees into investments that not a single trustee, consultant or staffer could explain?

Donor-advised funds are also a great way to give money to your favorite charity if you think their own investment

The article includes more clever advice:

... Donors who give appreciated assets get an added benefit: They avoid paying capital-gains taxes when they make the donation, and they get a deduction against their income taxes for the full value of the asset.If you paid $50 for stock, now worth $100, give the stock to your favorite charity (Hoover!). The charity gets $100, you take $100 off your taxes, but you don't pay capital gains taxes on the $50. Essentially you get to take $100 plus the capital gains tax as a deduction.

It gets better though. Give a non-market asset to your favorite charity. You can see both you and the charity have every incentive to report fanciful values for the asset. If it's really worth $100, well, call it $200 for the IRS. The charity still gets $100 for free.

Now you can actually make money out of donations. Conservation easement syndications (here, here and most fun here are even better. Buy land cheap, declare a huge value, put the land in a conservation trust, promising not to build houses on it -- actual operating golf courses are ok, and too bad if sometime in 2050 building some houses is a good idea -- and deduct the high value against other income.

the former Millstone golf course outside Greenville, S.C. Closed back in 2006, it sat vacant for a decade...In 2015, the owner put the property up for sale, asking $5.8 million. When there were no takers, he cut the price to $5.4 million in 2016.

Later in 2016, however, a pair of promoters appeared. They gathered investors who purchased the same parcel at the market price and, with the help of a private appraiser, declared it to be worth $41 million, nearly eight times its purchase price. Why? Because with that new valuation and a bit of paperwork, the investors were suddenly able to claim a tax deduction of $4 for each $1 they invested. ..

...A preliminary IRS analysis of syndicated partnerships this summer showed investors claimed an average of $9 in tax deductions for every dollar they invest.There are lots of ways to interpret all this. One can celebrate the creativity of the American tax lawyer and wealthy investor. Who said innovation has fled the US?

Obviously, I'm not such a fan. Even if you take a benign view -- the US likes to pass very high taxes for symbolic purposes, and then allows all sorts of shenanigans on the side so people don't actually have to pay the taxes -- much of the economic damage is done. Aside from the fact that marginal disincentives are high, the cost of all this stuff is not trivial either. From the first article

The funds linked to investment firms such as Fidelity and Vanguard typically charge administrative fees... The funds are often invested in vehicles managed by those firms and generate fees for the for-profit business.And the lawyers who set up conservation trusts, and the lobbyists who keep them in the tax code, are all taking their cut too.

But even that is not the most annoying part. Now, on top of everything else, a wise taxpayer needs to set up a donor advised fund, sign a bunch of papers, and manage it each year. Already, perfectly normal citizens have to have trusts to manage estates, and hundreds of pages of tax forms each year. The needless complexity of life in the Republic of Paperwork is, to me, the most annoying part. We need a grand simplification of our public life. If this is what it leads to, the whole charitable deduction thing should get tossed overboard.

Summary of study on well-being and self-control in the Irish population

Posted by Economist Channel on

Label:

On January 25, 2018, we presented new data on well-being and self-control in the Irish population at the Institute of Banking. We conducted a study using the Day Reconstruction Method (DRM) with Amarach Research and asked almost 1000 Irish individuals to tell us about three episodes they experienced “Yesterday”. Below are some graphs from the presentation and some further reading and offers a snapshot of the many potential uses of such data across contexts.

If you like to know more about the study or are interested in running similar studies yourself, please contact Liam Delaney (liam.delaney@ucd.ie) or Leonhard Lades (leonhard.lades@ucd.ie).

Illustrative findings:

Further reading:

If you like to know more about the study or are interested in running similar studies yourself, please contact Liam Delaney (liam.delaney@ucd.ie) or Leonhard Lades (leonhard.lades@ucd.ie).

Illustrative findings:

|

| Figure 1: Four experiences during the day. |

|

| Figure 2: When did people engage in different activities? |

|

| Figure 3: How positive did people feel during different activities? |

|